Translated by Sam Garrett

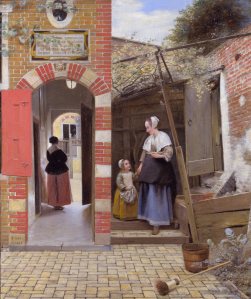

In Room 25 of The National Gallery is a painting by Pieter de Hooch, an artist who specialised in scenes of domesticity in the heart of the Dutch Golden Age. The Courtyard of a House in Delft (1658) presents a solid everyday world of cleanliness, transparency, upright citizenry, and carefully marshalled beatific children; a world of order and harmony founded on firm moral ground. This is, as Andrew Graham-Dixon writes, ‘a place where stillness and security are charged with ethical value…De Hooch’s courtyard is the setting for a gentle conflict between the virtues of domesticity and the forces ranged against them.’ This is the prosperous Dutch’s self-conception reflected for their moralising satisfaction and patronage. This is, they think, a form of happiness: clean, Calvinist, and destined for Heaven. Graham-Dixon goes on, ‘The safe enclosure of the home becomes an image of the safe enclosure of the state…To look out is to see, not difference, but sameness;…an entire city of safe havens, an urban organism made up of such healthy, single cells as the one he has happened to paint. Art becomes a form of civic self-assurance.’ It also becomes rather bland.

founded on firm moral ground. This is, as Andrew Graham-Dixon writes, ‘a place where stillness and security are charged with ethical value…De Hooch’s courtyard is the setting for a gentle conflict between the virtues of domesticity and the forces ranged against them.’ This is the prosperous Dutch’s self-conception reflected for their moralising satisfaction and patronage. This is, they think, a form of happiness: clean, Calvinist, and destined for Heaven. Graham-Dixon goes on, ‘The safe enclosure of the home becomes an image of the safe enclosure of the state…To look out is to see, not difference, but sameness;…an entire city of safe havens, an urban organism made up of such healthy, single cells as the one he has happened to paint. Art becomes a form of civic self-assurance.’ It also becomes rather bland.

Johannes Vermeer’s The Little Street was finished in the same year, in the same historical moment as The Courtyard of a House in Delft and resembles it in subject, but whereas De Hooch’s work encapsulates Holland’s vision of itself in both the 17th and 21st Centuries, Vermeer’s interrogates the façade and allows darkness and indeterminacy to remain in both home and the individual. Now we are on the outside looking in. At a time of unparalleled prosperity, Vermeer just might be wondering what lies beneath the mercantile frontage, beneath the blurred faces of his retiring subjects. Graham-Dixon calls this ‘the way in which the world withholds itself from the artist-as-observer, the way in which it retains its mystery.’ We might also see those sheer frontages as dykes holding back that darkness as the pumps and levees resist the North Sea and ensure Holland’s feet are kept dry.

Johannes Vermeer’s The Little Street was finished in the same year, in the same historical moment as The Courtyard of a House in Delft and resembles it in subject, but whereas De Hooch’s work encapsulates Holland’s vision of itself in both the 17th and 21st Centuries, Vermeer’s interrogates the façade and allows darkness and indeterminacy to remain in both home and the individual. Now we are on the outside looking in. At a time of unparalleled prosperity, Vermeer just might be wondering what lies beneath the mercantile frontage, beneath the blurred faces of his retiring subjects. Graham-Dixon calls this ‘the way in which the world withholds itself from the artist-as-observer, the way in which it retains its mystery.’ We might also see those sheer frontages as dykes holding back that darkness as the pumps and levees resist the North Sea and ensure Holland’s feet are kept dry.

All I want to talk about here are the things I heard and saw during our little get-together at the restaurant.

Herman Koch’s The Dinner can be understood as a challenge to the de Hoochian picture of Holland, happiness, and human nature; and as an attempt to move past Vermeer’s allusions to darkness into those shadows themselves. It goes without saying that Paul Lohman wants to talk about far more than what he heard and saw on one evening in an expensive Amsterdam restaurant. He is far from being a neutral narrator and he wants us to understand how he, his wife Claire, his sister-in-law Babette, and prominent politician of a brother Serge ended up sitting at this table, talking about the things their children have done and what they are to do about it. Whether Paul is reliable or not is not entirely clear; although I suspect that his honesty is one of the unsettling aspects of the novel. His voice, whilst becoming increasingly violent and disturbing, does satisfy that terrible phrase but laudable characteristic of being compulsively readable. In deceptively simple tones Koch has Paul narrate the evening and its unexpected developments.

‘The crayfish are dressed in a vinaigrette of tarragon and baby green onions,’ said the manager: he was at Serge’s plate now, pointing with his pinkie. ‘And these are chanterelles from the Vosges.’

The Dinner begins as an apparent consideration of a certain brand of conspicuous consumption and artifice. That the novel is anchored by the framework of the meal’s five courses – Aperitif, Appetizer, Main Course, Dessert, Digestif – seems to support this. Indeed, Paul rails against the absurd divorce between price and service in top restaurants, against the stage-management, wine-urging manipulation, and his brother’s political smile. We sympathise, even if Paul is more strident than we might be. ‘Serge never reserves a table three months in advance. Serge makes the reservation on the day itself, he says he things of it as a sport.’ This is far from the moralising pictures of Pieter de Hooch. It recalls, rather, the other side of the Golden Age: the conspicuous consumption of Frans Hals’ Banquet of the officers of the St George Militia Company (1616) and Willem Kalf’s Still Life with the drinking horn of the St Sebastian Archers’ Guild, lobster and glasses (c.1653) Serge Lohman wants to show off, to say ‘Look, I can have this whenever I want, because I can play the game’; or so his brother believes. Slowly the meal becomes an exercise in manoeuvring for advantage amongst the diners, from course choice to strategic toilet breaks. It quickly becomes clear that far more is at stake than simple brotherly conflict or cultural bankruptcy as parents jockey for position and each course ramps up the tension in simmering mix of violence, loyalty, moral indignation, and desire for stimulation.

Indeed, Paul rails against the absurd divorce between price and service in top restaurants, against the stage-management, wine-urging manipulation, and his brother’s political smile. We sympathise, even if Paul is more strident than we might be. ‘Serge never reserves a table three months in advance. Serge makes the reservation on the day itself, he says he things of it as a sport.’ This is far from the moralising pictures of Pieter de Hooch. It recalls, rather, the other side of the Golden Age: the conspicuous consumption of Frans Hals’ Banquet of the officers of the St George Militia Company (1616) and Willem Kalf’s Still Life with the drinking horn of the St Sebastian Archers’ Guild, lobster and glasses (c.1653) Serge Lohman wants to show off, to say ‘Look, I can have this whenever I want, because I can play the game’; or so his brother believes. Slowly the meal becomes an exercise in manoeuvring for advantage amongst the diners, from course choice to strategic toilet breaks. It quickly becomes clear that far more is at stake than simple brotherly conflict or cultural bankruptcy as parents jockey for position and each course ramps up the tension in simmering mix of violence, loyalty, moral indignation, and desire for stimulation.

I was remarkably calm. Calm and fatigued. There would be no violence. It was like a storm coming up: the café chairs are carried inside, the awnings are rolled up, but nothing happens. The storm passes over. And, at the same time, that’s too bad. After all, we would all rather see the roofs ripped from the houses, the trees uprooted and tossed through the air; documentaries about tornados, hurricanes and tsunamis have a soothing effect. Of course it’s terrible, we’ve all be taught to say that we think it’s terrible, but a world without disasters and violence—be it the violence of nature or that of muscle and blood—would be the truly unbearable thing.

The literary interrogation of the dark side of humanity goes at least as far back as Mary Shelley and Robert Louis-Stevenson, whilst its dramatic consideration is thousands of years old. More recently James Smythe’s The Machine, a speculative re-examination of the Frankenstein story – amongst many other things – ask what it is which keeps violence at bay, and what it takes for those barriers to be overtopped: ‘People are capable of anything, he says. It’s inside all of us.’ In many ways The Dinner is akin to Golding’s Lord of the Flies in that Koch uses children as well as adults in order to pose his questions, although it is, in a limited way, more effective because the novel remains rooted in the modern state rather than a desert island. The novel becomes concerned with the nature of moral responsibility and the lengths to which parents should go in order to protect their children from themselves and the codes of the society in which they live.

‘To the outside world they’re suddenly adults, because they did something that we, as adults, consider a crime. But I feel that they’ve responded to it more like children. That’s exactly what I was trying to tell Serge. That we don’t have the right to take away their childhood, simply because, according to our norms, as adults, it’s a crime you should have to pay for for the rest of your life.’

The repressed violence and cold manipulation that infects and bursts out of the characters in The Dinner is chilling. ‘To look out is to see, not difference, but sameness.’ Are the Lohmans an aberration or a microcosm? Is their darkly rationalised happiness won in a way which parallels the self-deception of a nation? De Hooch’s domestic harmony, his network of safe-havens hide something far darker. The Golden Age was built on the proceeds of the slave-trade. It is hard not to see a parallel here with the son Serge and Babette adopted from Burkina Faso. His treatment is troubling and the potentially political or honest intentions of his adoptive parents unresolved. What stands behind Vermeer’s shuttered windows and dark doorways? What is being kept at bay?

Without knowing glances—without winks—there was in fact no secret: that was my reasoning. It might be hard for us to put the events in the cubicle out of our minds, but in the course of time they would start to exist outside us—just they did for other people. But what we did have to forget was the secret. And the best thing was to start forgetting as soon as possible.

Koch shifts the ground beneath the reader as more and more is revealed throughout The Dinner, as the meal runs its course. It is very well done indeed. The sympathies of the reader veer wildly after an initial identification with Paul’s impatience with the paraphernalia of consumption; an identification which becomes increasingly uncomfortable in the face of Koch’s uncompromising writing. The Dinner is nothing if not gripping, even if elements stretch one’s credulity a little. The half-cocked idea that not all victims are innocents and not all criminals are guilty unsettles and shifts throughout as it is put to self-interested use. The tablet suffering a good-natured assault by a questing limb of ivy in de Hooch’s picture runs thus, ‘This is in Saint Jerome’s vale, if you wish to repair to patience and meekness. For we must first descend if we wish to be raised.’ The choices Paul and Claire make in order to protect their family might ultimately twist this moralising saying into a darker reflection of itself. Happiness is, after all, its own sensation.

The Dinner is published in paperback by Atlantic.

Pingback: What can we read into the food served in the Dinner blog tour | Winstonsdad's Blog

Pingback: Dinner Conversation | Robin's Books

This is such a good review I’m almost put off reading the book, since after finishing it I’d have to write it up on my own blog and it wouldn’t compare. Lovely use of Dutch art.

My only concern with this book is whether the conceit is sufficiently robust to last what seems a reasonably lengthy book. Put another way, does it outstay its welcome? I’m also a bit leary simply as I tend not to be especially fond of books that ultimately feel contrived or depend on a twist (though I’m getting the impression this isn’t a twist novel thankfully, contrived possibly though).

Is there a reason everyone stays until the digestif?

Thanks – I usually think exactly that when I read your reviews. Having let the book settle I might be a little more ambivalent about some aspects of the book, but not in most of my analysis. There are aspects which might not be as believable as all that, and there are a few bits one might call revelations rather than twists. That everyone stays until the digestif is one of the unsettling aspects, although the reasons for that become apparent, I think. If you do read it I’d be keen to hear what you think. I’ve had some good discussions about it with people. Plenty I didn’t mention.

Pingback: The Dinner by Herman Koch – Farm Lane Books Blog

Pingback: February, thus far | Other Sashas