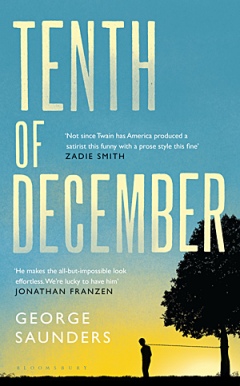

On Monday 10th March George Saunders won the inaugural Folio Prize for Tenth of December. Announcing the winner, Chair of the Judges Lavinia Greenlaw, said:

“George Saunders’s stories are both artful and profound. Darkly playful, they take us to the edge of some of the most difficult questions of our time and force us to consider what lies behind and beyond them. His subject is the human self under ordinary and extraordinary pressure. His worlds are heightened versions of our own, full of inexorable confrontations from which we are not easily released. Unflinching, delightful, adventurous, compassionate, he is a true original whose work is absolutely of the moment. We have no doubt that these stories will prove only more essential in years to come.”

I reviewed Tenth of December on release in early 2013. I liked it:

A fundamentally optimistic satirist is hard to find. A satirist who is fundamentally optimistic and actually funny is even more elusive. Yet in Tenth of December George Saunders presents a plural and intensely humane collection of stories which probe the dynamics of motivation, self-consciousness, violence, and the abuse of language in supple prose which unfailingly captures the diverse voices of characters in sore need of an entirely feasible redemption. And it’s funny.

The opening and closing stories explore the different ways that language aids us in gaining traction on the world. In ‘Victory Lap’ a young girl’s emotional and linguistic naivety is shattered by a foiled assault, her rescuer repressed by the internalised edicts of his parents, his only release the strings of swear-words he composes. Here is the first hint of Saunders’ concern with the structures of thought which constrain action. That theme continues in the title story, where a boy for whom the world overflows with voices and a dying man for whom that world has narrowed to a cancerous point cross paths in the snow. In the process, how each meets the world changes, as the voices and concerns of one recede, and those of the other, in a manner quite distinct, begin to reassert themselves.

‘His aplomb threw them loops.’ I really like this sentence. It bubbles and flows and is simply happy. Anyway.

‘Escape from Spiderhead’ is in many ways the heart of the collection. It considers the commercial manipulation of thought and feeling in a grim caricature set in a penal laboratory where powerful drugs with eerily familiar names like ‘VerbaLuce’, ‘Vivistif’, and ‘Darkenfloxx’ are mainlined by human guinea pigs for whom the sheen of agency resides in their apparent freedom to ‘acknowledge’. The endurance of conscience throughout this harsh story of chemical manipulation is testament to Saunders’ belief that goodness is our natural state. False reductions of crime or of love are damaging, for what you can reduce a thing to is far from being that which you destroyed in the analysis.

In ‘Sticks’ Saunders encompasses an entire life and the contingency of its expression in two pages ostensibly about a metal pole and its various accessories. The different brands of irresponsibility and their problematic reduction to a deficit of love or kindness are addressed in ‘Puppy’, which opens with one of my favourite paragraphs from the collection: at once rhythmic, amusing, and insightful.

Twice already Marie had pointed out the brilliance of the autumnal sun on the perfect field of corn, because the brilliance of the autumnal sun on the perfect field of corn put her in mind of a haunted house—not a haunted house she had ever actually seen but the mythical one that sometimes appeared in her mind (with adjacent graveyard and a cat on a fence) whenever she saw the brilliance of the autumnal sun on the perfect etc., etc.—and she wanted to make sure that, if the kids had a corresponding mythical haunted house that appeared in their minds whenever they saw the brilliance of the etc., etc., it would come up now, so that they could all experience it together, like friends, like college friends on a road trip, sans pot, ha ha ha!

That insecurity inflected need for shared experience in the face of well-intentioned failure develops in ‘Al Roosten’ wherein the eponymous sufferer of an inferiority complex shifts and twists under the world’s gaze and finds himself exhausted by reflection. ‘My Chivalric Fiasco’ echoes ‘Spiderhead’ and contains moments of pure brilliance as a medieval theme park employee’s day goes completely wrong under the influence of ‘KnightLyfe®’: an aid to improvisation which moulds not just its consumer’s vocabulary but their moral compass as well.

Did I want all home? I did. I wanted all, even the babies, to see and participate and be sorry for what had happened to me.

The most haunting and topical story is ‘Home’ in which ‘the power of recent dark experience’ emerges in the slowly discomfiting revelation of an Iraq veteran’s loss of self and the struggle to reintegrate on his post-court-martial return. His filter between thought and action has dissolved and brings him closer to the baby he isn’t allowed to hold than to those around him, each of whom thanks him for his service in such a way that it becomes a meaningless beat in an awkward conversation for a man who has lost almost all sense of home. The kernel which yearns to return is what makes this story heartbreaking.

Throughout Tenth of December Saunders resists the reduction of human behaviour to the things which condition our lives: drugs, military service, background, and language. Each constrains, but not irredeemably; and that possibility of redemption underpins a belief in a kind of prelapsarian goodness. Yet Saunders’ optimism isn’t metaphysical. It is here and now that we can do that tiny bit better. A plea for a common but plural humanity in the face of a thousand natural shocks, Tenth of December is a consummate collection which I thoroughly recommend.

Tenth of December is published by Bloomsbury.

My thanks to Bloomsbury for this review copy.