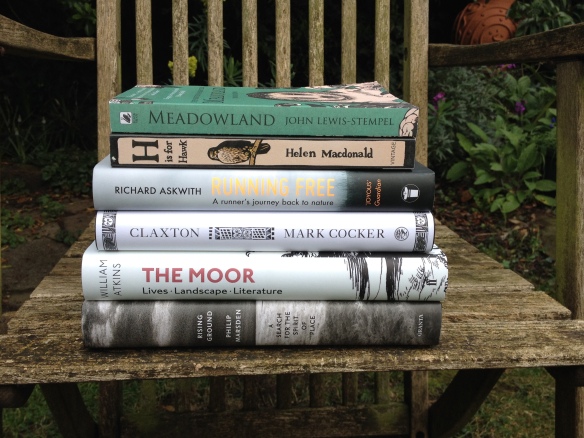

I wrote in my last post about reading the Thwaites Wainwright Shortlist as a way to further my understanding and engagement with landscape and the environment. (Not to mention the opportunity to read some very good writing). It’s going to take me a little while: This is resolutely unrushable writing in both form and content. Except, perhaps, for Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk which is a tumbling, headlong dive into grief, reconciliation, and the nature of wildness and the bond between human and animal. It contains some of the finest writing I’ve come across in quite a while. It’s won everything else, but I wouldn’t bet against it come the ceremony.

I wrote in my last post about naming, acquaintance, and experience: fitting, then, that I should start John Lewis-Stempel’s Meadowland: The Private Life of an English Field, a book packed with latin and local names for the grasses, flowers, trees, birds, moles, rodents, bats, beetles, earthworms, and more which populate a Herefordshire field throughout the year. For example, in Lower Meadow one might find “of grasses alone, timothy, meadow fescue, cock’s foot, meadow foxtail, woodrush, sweet vernal, tufted hair-grass, crested dog’s tail and meadow grass.” This way of looking, to echo John Berger, married as it is with a streak of hard-nosed romanticism, emerges from a farmer’s engagement with the land. As Lewis-Stempel writes, “There is nothing like working the land for growing and reaping lines of prose.”

What is so striking about Meadowland is the concentration of experience and knowledge poured into a single field and recorded over the course of the year. Lewis-Stempel emphasises from the outset that his is a record of a kind of affective experience (“I can only tell you how it felt. How it was to work and watch a field and be connected to everything that was in it, and ever had been”): something which can generate some remarkable moments enmeshed in the life of the meadow as well as the occasional platitude and odd turn of phrase as the writer overreaches in the search for expression.

Yet, if one candidate for beauty is what Monroe Beardsley called “unity in diversity”, then Meadowland succeeds admirably in capturing the variety within the web of the meadow, even as the grasses are strewn with dew-lapped webs of another kind. Lewis-Stempel doesn’t shy away from the death which pervades the landscape: there is a particularly unpleasant squashed baby sugar mouse incident and the writer walks out gun in hand more than once. But from the print of that mouse-breaking cow’s hoof is born a microclimate which supports specialised fauna: as an intimate portrait of a rich and potentially threatened rural space Meadowland succeeds admirably.

The moor ahead of me was a foaming, surging mass, a sponge squeezing itself, a waterlogged lung. I could feel its spume coming down on me, hear its roar.

Next up for me is William Atkins’s The Moor: Lives, Landscape, Literature which tracks the moorland of mainland Britain from the Southwest to the Northeast through history, fiction, and the author’s journey. Thus far, Atkin’s writing is very impressive indeed. At a recent Faber Social Robert Macfarlane discussed the problem of moving from qualia–or the texture of conscious experience–to style, to a form of expression that conveys something of our phenomenology. Atkins succeeds, I think, in evoking not just the sensory experience, but what–if we were that way inclined and aiming for pretension–we might call the “semantic cloud” of experience: the images, allusions, and atmosphere that we supply in our engagement with our surroundings. (There is a Sebaldian influence hovering in the background, emphasised by the occasional telescoping of time.) Atkins populates this cloud with moors murders, hopeless Victorian schemes to tame the landscape, Henry Williamson’s Tarka the Otter, Du Maurier’s Jamaica Inn, and the “black pits” of R. D. Blackmore’s Lorna Doone. It’s working for me so far.

The mist, secretly, had become fog, a deadening vapour that surged with the wind and seemed a presence as constant and primary as the peat underfoot. It was water with a rinsing of soap, an occlusion rather than a blinding. My cough sounded like an animal’s — in these conditions a noise lasts no longer than its cause.

I’m fortunate to be able to run a competition to win a set of the Thwaites Wainwright Prize shortlist. Why should you read these books? I asked the judges what draws them to the kind of writing the prize seeks to promote, why its valuable, and what they are looking for when judging submissions. More to come in my report on the ceremony, but here are the thoughts of two of the jury.

Chair of judges, Dame Fiona Reynolds

I can never get enough of nature writing. I love the way I am drawn, irresistibly, into the place or the subject of the author’s passion, inspired by the craft of writing and the quality of observation.

Fergus Collins, judge and editor of BBC Countryfile magazine

As a country boy living in London and then Bristol, I found the words of great nature writers such as Richard Jefferies or Ian Niall a wonderful escape from endless tube journeys and concrete skylines. They inspired me to be more observant about my wild neighbours even in the depths of the city. But as well as conjuring atmosphere and magical encounters, such exceptional writing should sometimes be as challenging and discomforting as the natural world so often is – and of which the reader is a part.

To enter the competition just leave a comment below, being sure to include an email address. The winner of the Thwaites Wainwright Prize is announced on the evening of Wednesday 22nd April. I will accept entries for the shortlist competition until midnight on Friday 24th April. I’m afraid that I can only accept UK entries. The winner will be chosen using a random number generator.

The competition is closed and a winner has been selected.