The Thwaites Wainwright Prize Shortlist

I have an odd relationship with nature and landscape writing. Naming, as any poet will tell you—I remember Carol Ann Duffy saying something to this effect—is a powerful thing. Through their parts or as wholes, names set off small semantic explosions in the mind of the reader as well as serving to anchor poetic abstraction in places, things, and people. Clive James’s Japanese Maple, Alice Oswald’s Severn, Heaney’s Mossbawn, miscellaneous Wordsworth: each by its naming puts out little tendrils which hold the world close. That, I think, is what I find attractive about writing on place, nature, landscape, and wildlife: its naming and exploration of things named.

Yet, this interest can feel like bad faith. It is because I am so poor at naming plants, birds, trees, and landscape—chalk hills? Clay? Limestone?—that I find this writing so fascinating, so enchanting. Of course, the history and human relationships bound up in landscape and wildlife are deeply interesting, and I love good writing about them; but, nonetheless, it is the power of naming, built on a way of perceiving I lack that lies at the heart of my worry.

Such writing has for me something of the allure of fantasy or science fiction: the exploration and evocation of another world, where most of the world-building has been taken care of by history and the environment, though interpretation and projection by the writer certainly has its part to play. Writers who can draw on language and knowledge I’ve never known or which seems to vanish as soon as I hear it. (Expressed in a rather flippant poem—but the anxiety is more substantial.) Roger Deakin wanders about discussing blackthorn, coppicing, insects, beetles, and really rather a large variety of birds; Robert Macfarlane springs up and down hills, across moors and tidal pathways, with a dictionary in tow: that’s how it feels anyway. Helen Macdonald and J. A. Baker name the birds and understand the goshawk and peregrine. I struggle to remember the difference between blue tits and great tits, ash and bay, which hills are where and what they are made of. (I’m beginning to grasp the South Downs.)

All of this bothers me because each of these writers hints at a way of perceiving that feels lost. If you can name things you can understand the relations between them—and vice versa—and that understanding can penetrate your perception of the environment and its history. This capacity enchants me as a mystery does: like a magic trick, I can’t see how it’s done, although I can think it impressive or beautiful: the bad faith worry stems from the sense that—as with the magic trick—learning how its done might lead to disenchantment. I don’t think that would happen; in fact, I expect it would be quite the reverse. Acquaintance would enrich rather than diminish, because naming and understanding aren’t sleights.

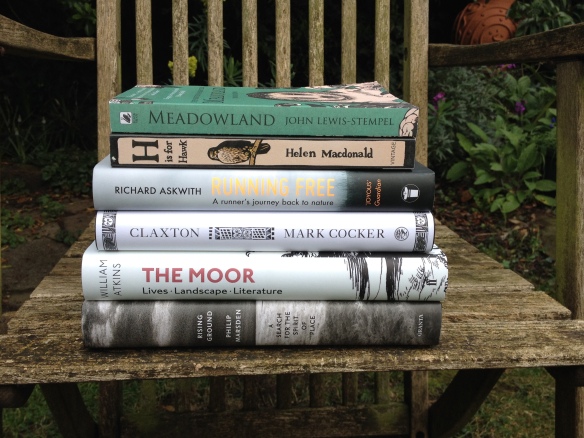

In order to deepen my acquaintance I’m going to be reading the Thwaites Wainwright Prize shortlist over the next few weeks. I’ve read the wonderful H is for Hawk already—and you really must—and the rest of the shortlist is a cross-section of the kind of writing I’ve been considering: place, people, wildlife, and their histories and crossings. I’m starting with Meadowland: The Private Life of an English Field by John Lewis-Stempel in my attempt to move beyond all that undifferentiated green.

- Running Free: A Runner’s Journey Back to Nature, Richard Askwith (Vintage/Yellow Jersey).

- The Moor: Lives Landscape Literature, William Atkins (Faber & Faber).

- Claxton: Field Notes from a Small Planet, Mark Cocker (Vintage).

- Meadowland: The Private Life of an English Field, John Lewis-Stempel (Transworld).

- H is for Hawk, Helen Macdonald (Vintage).

- Rising Ground: A Search for the Spirit of Place, Philip Marsden (Granta).